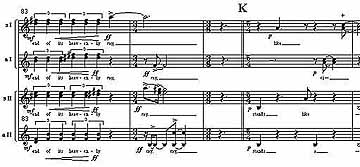

Gebet

Nacht, stille Nacht, in die verwoben sind

ganz weiße Dinge, rote, bunte Dinge,

verstreute Farben, die erhoben sind

zu Einem Dunkel Einer Stille,— bringe

doch mich auch in Beziehung zu dem Vielen,

das du erwirbst und überredest. Spielen

denn meine Sinne noch zu sehr mit Licht?

Würde sich denn mein Angesicht

noch immer störend von den Gegenständen

abheben? Urteile nach meinen Händen:

Liegen sie nicht wie Werkzeug da und Ding?

Ist nicht der Ring selbst schlicht

an meiner Hand, und liegt das Licht

nicht ganz so, voll Vertrauen, über ihnen,—

als ob sie Wege wären, die, beschienen,

nicht anders sich verzweigen, als im Dunkel? . .

.

Rainer Maria

Rilke

aus: Das Buch der Bilder

|

Prayer

Night, silent night, in which are woven

wholly white things, red, colorful things,

scattered colors that have been elevated

to one Darkness, one Silence,— bring

me too into relationship with the Many

which you have persuaded and acquired. Do

my senses still play too much with the light?

Does my countenance from the surrounding

objects still bring disturbance

into relief? Pass judgement upon my hands:

Do they not lie there like tools, like things?

Is not even the ring common

upon my hand, and does not the light

shine so completely, full of trust, upon them,—

as if they were paths, which, when illumined,

branch not differently, as when in darkness? . . .

(tr. Cliff Crego)

from: The Book

of Images

|